AWARD-WINNING AUTHOR AND JOURNALIST

AWARD-WINNING AUTHOR AND JOURNALIST

QUEEN OF THE PEOPLE

BY LYDIA MARTÍN

Originally Published in Presenting Celia Cruz

Author: Alexis Rodriguez-Duarte

Date: 2006

ISBN-10: 140008203X

ISBN-13: 978-1400082032

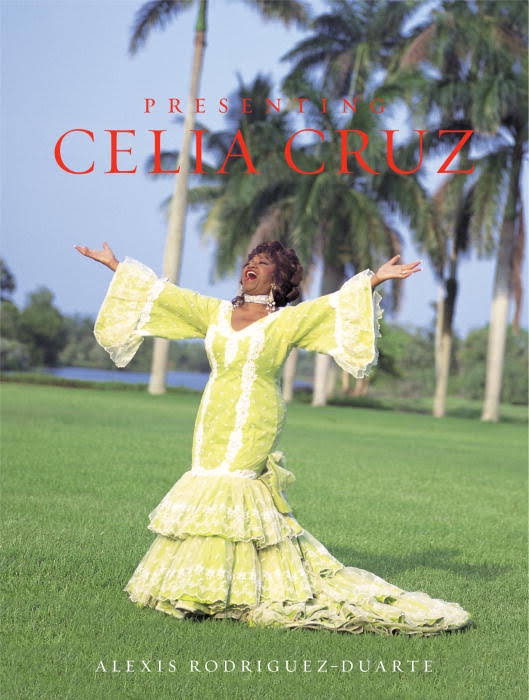

It seems like a lifetime ago that I stood at the opening of Alexis Rodriguez-Duarte’s Cuba Out of Cuba exhibit in Miami, fixated on a lush black-and-white of Celia Cruz surrounded by royal palms. (It is part of the series that produced the cover of this book.) The trees may have stretched 50 feet, but I still see Celia towering over them, that huge, joyous energy of hers willing those giant fronds to dance with the sky.

What that photo captures best is Celia’s endless force. But it also led me to a heart-stopping thought. Celia didn’t make it to that 1997 opening because she couldn’t get away from Mexico, where she was working on a soap opera. But she sent a video congratulating Alexis and partner Tico Torres, who styled the shoots. While we all watched, I turned to Liz Balmaseda, my friend and colleague, and whispered something crazy.

“Can you imagine what will happen the day Celia dies?”

It stuck in my throat. We looked at each other, both taken aback by a thought that had never entered our minds. Celia leaving us was unfathomable. It would be huge, we knew that. We also knew it would be a lifetime away.

In retrospect, it came much too swiftly. And it was even bigger and more resounding than we could have imagined that night. Celia was son. She was salsa. She was the music that reached our very core, even when our core went wandering toward new languages and new rhythms. She was the essence of azúcar. And the soul of congas that have been pounding since ancestral times.

More than that, Celia was family.

She was the voice that kept me Cuban when I was a kid growing up in Flint, Michigan, where in the 1970s there was not a strain of Latin music on radio. Not a single Spanish-language TV channel. In fact, there were no Latin people. And I, like so many other immigrant kids all over the country, was trying desperately to fit in. For a child who didn’t know better, becoming American meant casting off the Cuban part.

But Celia refused to let that happen. I didn’t want to hear much about the island where I was born. But when my mother played her old Celia Cruz LPs- usually on frozen Sunday mornings while she baked Cuban bread because there was not a single place to buy it–that powerful voice took hold of a lite 10-year-old who was obsessed with rock and roll.

My mother labored to ensure I didn’t forget my first language. But it was Celia’s songs that demanded I hang on to my culture. From the first strains of “Químbara.””Bemba Colorá,” Yerberito Moderno,” I was gripped by recognition.

Icons are like that. They embody who we are. They stand as our collective soul. But whatever she meant to the Cuban family in the snowy Midwest, she also meant to the Dominican family in the Bronx, the Colombian family in Atlanta, the Panamanian family in Miami. Because that’s the other thing about icons-they transcend.

And perhaps more than any other icon, Celia Cruz had the reach of infinite royal palms. Marilyn Monroe was an icon, but she represented a certain milieu. Elvis was an icon, but he was also framed by a certain moment that meant a certain thing about a certain type of American. Celia blasted through the eras and the borders. As Cuban as she was, she belonged to the world. She was an icon to all kinds of Americans. An icon not to one, but to several generations of Latin Americans, Europeans, Africans, even Asians.

Watch the video for Celia’s last huge hit, 2002’s La negra tiene tumbao. Watch her, at 76, belt out the lyrics to the sizzling tune that blends traditional tropical with hip-hop. Watch her in that punky tangerine-orange wig, a bronzed naked girl sauntering in the background and a hip-hopper spitting rhymes at her side, and you understand that Celia may have been Old Cuba, but she was as hip as MTV.

She became a star in the 1950s. But there was not a decade since that did not bear the stamp of Celia Cruz. She had hits in her 20s. She had hits in her 70s. She had hits, endless hits, all the way through a career that spanned six decades and produced nearly 100 albums. She cut across nationalities, ages, races. She was as fierce to the aging soneros as she was to the salseros, the merengueros, the rockers and the hip-hoppers.

And that is why, when Celia Cruz was finally silenced on July 16, 2003, mourners flooded the streets of Miami and New York for twin funerals the likes of which neither city had seen in modern times. That Celia Cruz, a black Latin woman from a small Caribbean island, could bring New York City’s Fifth Avenue to a standstill says everything about her magnitude.

In Miami, mourners stood in lines that stretched dozens of city blocks for a chance to pay last respects at the storied Freedom Tower, where Celia lay in state. There were endless Cuban flags, Haitian flags, Jamaican flags, Puerto Rican flags, Venezuelan flags, Mexican flags, even British and Canadian flags, all waving along with the Red, White & Blue.

In New York, funeral directors who handled the historic Judy Garland wake in 1969, the wake they had called their biggest, stood wide-eyed as thousands upon thousands turned out for Celia. Garland’s funeral had been huge. But it could not compare to Celia’s, they said.

Why we loved her is not as simple as saying that her music moved us. Or that her sky-high wigs and nine-inch heels made us cheer the second she burst onto a stage. There is definitely that. We could not take our eyes off her. She was the essence of Latin femininity, a woman who didn’t fear her Yoruba-goddess voluptuousness. But also a woman who didn’t fear being louder, stronger and more brash than the men who ruled salsa. We loved her for all of that. We loved the way her rumba stepping made our spirits soar.

But we also loved her because she was one of the world’s most accessible superstars. Long before I met Celia, I knew her. The masses who never met her, they also knew her. Not that she ever paraded the details of her private life. Celia was way too Old School for that. But for all the eye-popping wigs and gowns and shoes, there was never any artifice. Fame can warp a lot of people as persona gets away from person. Lesser divas melt under the pressures of celebrity. Celia grew stronger.

You can’t say she wasn’t in touch with her fame. She understood her place in history. But she had the grace of a goddess who had grown comfortable with her powers. I’ve interviewed endless celebrities and have suffered endless egos. I still remember one of my first interviews with Celia in New York. We spoke hours more than I thought she would be willing to give me. And then when I tried to say goodbye, she invited me to come along for dinner at Victor’s Café, where she was celebrating her sister Gladys’ birthday. After an amazing evening, Celia and her sister singing bits of old boleros, trying to outdo each other’s memories, I went to give her a kiss and say goodnight on the curb. I planned to take a cab back to my hotel. But Celia wouldn’t hear of it.

She made her driver go out of the way so I didn’t have to deal with the madness of Manhattan. As the limo dropped me off, Celia asked if I was planning to go out again that night. “Um, maybe.” I hesitated the way I might have if she had been my grandmother. She gave me a stern little look that said I really should stay in.

“Well, don’t take that bag with you,” she finally said with a sigh. “Just take some money in your pocket. And don’t stay out too late. This city can be dangerous.”

We loved Celia because she mastered the art of being a diva. But we also loved Celia because she mastered the art of being one of us.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Lydia Martín is an award-winning fiction writer and journalist who spent 25 years covering Miami’s growth and cultural evolution for The Miami Herald. She was part of the team that won a Pulitzer Prize for coverage of Hurricane Andrew. She was twice a finalist for journalism’s Livingston Award, and won a GLAAD Media Award for Spanish-language magazine writing. She also won the 2016 Ploughshares Emerging Writer contest for fiction; and the 2016 Editor’s Prize from Fifth Wednesday Journal, which nominated her for a Pushcart Prize.