AWARD-WINNING AUTHOR AND JOURNALIST

AWARD-WINNING AUTHOR AND JOURNALIST

PAPER BOATS

BY LYDIA MARTÍN

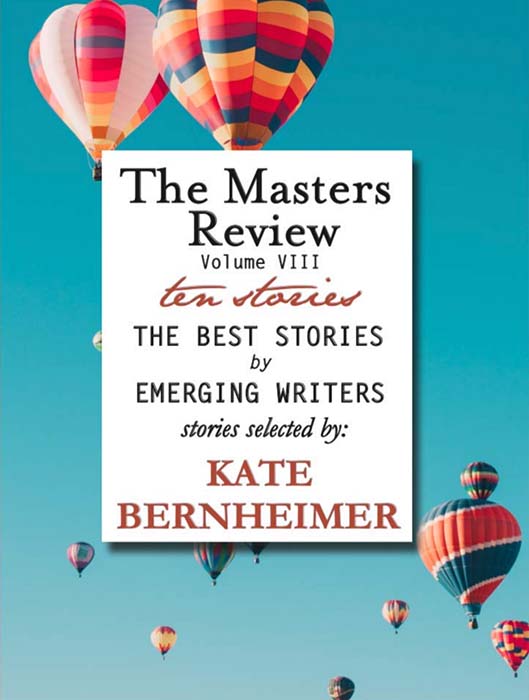

Originally Published in The Masters Review Volume VIII: Ten Stories, The Best Stories by Emerging Writers

Author: Kate Bernheimer

Date: December 2019

ISBN-10: 0985340770

ISBN-13: 9780985340773

The quimbombó had a stink to it that Felipe Mirabal couldn’t pinpoint. He walked into the cooler to sniff what remained of the ground pork the cook had used. But the pork was virtuous. And Felipe had received the okra himself early that morning—two crates full of fuzzy, bright green pods that snapped cleanly in half

with the slightest pressure of his thumb.

“Okra on the stove always smells a little manly. Like—well, you know like what,” said Rufino the cook, and the other guys guffawed.

“Álvaro, grab that pot!” Felipe threw elbow-length mitts to the brawniest guy in the kitchen, a Cuban rafter who had paddled strung-together inner tubes onto a rocky beach in the Upper Keys a year earlier.

The paddle Álvaro wielded now came from a kitchen supply store and was for flipping long strips of pork-back frying in a tank of lard that perpetually brimmed over, a thin layer of the stuff always congealing underfoot, making Álvaro’s workstation as treacherous as an ice rink. But those crunchy, salty chicharrones, sold from the walk-up window in brown paper bags that quickly turned translucent from the grease, remained the runaway hit at Restaurante La Rampa, at the southern tip of Miami Beach.

“Take it to the dumpster! Sí, sí—pot and all!” Felipe, his silver hair in a pompadour, a black comb always tucked into the breast pocket of his impeccable white shirts, threw himself against the back door and held it open.

He had run a scrupulous kitchen from day one. But lately, no matter how he tried to stay on top of things, there seemed to be more and more ugly little surprises. He was starting to think someone wanted to sabotage his business. It had to be someone right under his nose. Last week, he had been forced to pour ten gallons of milk down the drain. Someone playing games had unplugged the front cooler the night before.

And there was the incident a week before that, which Felipe still couldn’t get out of his head. He was about to bite into a steak sandwich, his tie thrown over his shoulder, when a rat the size of a well-fed kitten scampered across the lunch counter. Only Felipe and the waiter who had brought his sandwich saw it.

In the early 1990s, the southernmost streets of South Beach hadn’t yet caught the renaissance fever flaring a few blocks to the north, where decrepit Art Deco hotels were getting splashed in fresh pastels and out-of-towners were snatching boarded-up buildings like they were dollar-store souvenirs. The famous fashion photographers and the packs of models were constantly descending, elbowing one another for sexy backdrop. If you could call the subtropical decay they chased sexy.

And now there was talk of luxury condo towers going up near La Rampa. The restaurant’s tiny south-of-Fifth enclave, hugged by the ocean on one side and the bay on the other, and lapped at its tip by the wake of cruise ships crossing Government Cut channel, had grown seedier and seedier since the Beach’s last heyday back in the 1960s. Once the sun went down, you knew better than to be on foot there.

The restaurant still drew crowds, thank God. La Rampa and Joe’s Stone Crab down the street were about the only life left in Miami Beach’s oldest subdivision. But Felipe knew there’d be no stopping developers who were already sewing together parcels of land. The four squat apartment buildings across the street and the bodega next to it had already been knocked down, their flattened lots sending up garbage and grit whenever a big enough breeze

blew off the Atlantic. City officials hadn’t yet approved the idea of high-rises cluttering Felipe’s piece of sky. But Miami Beach was suddenly drunk on its own promise—of course they’d vote to let the developers build as high as they pleased. That’s why Felipe was pretty sure someone wanted his restaurant to fail, so he would be forced to sell for cheap. His parking lot alone took up more than half an acre.

* * *

“There are just too many strange things happening,” he told his son, Luisito, who was driving them to see another rundown house for sale in mainland Miami. “Today with the quimbombó—how could it have spoiled like that? And what about that rat a couple of weeks ago? I’ve seen a lot of greasy kitchen rats in my time. That was no kitchen rat!”

“What are you saying, Papi? A rat is a rat.”

“No, mijito. That rat looked like somebody’s pet! I’m telling you, somebody wants to ruin me.”

“You mean you think someone planted the rat? Por favor, Papi! Where do you get these things?”

Luisito was fresh from his evening workout, his salon-sculpted hair still damp and the V-neck of his designer t-shirt too plunging for his father’s taste, he knew. He downshifted and punched the accelerator to make the light at Biscayne Boulevard and Thirty-Sixth Street. They shot north, past hookers, crackheads, slummy motels with crisp midcentury modern lines.

“Two Ivy League degrees and what do you understand about life? Espabila, mijo! Wake up already! And why are you taking me to see another shitty house in the same bad neighborhood?” Felipe had promised to give Luisito a down payment for the right investment, but the three houses he had seen so far were nothing but dumps.

Felipe and his son had been close once. When Luisito was a boy, he’d settle into the crook of Felipe’s arm to watch TV while his mother Rosalina baked flans for the restaurant, flooding the house with the warm scent of caramel and vanilla. When he was about to turn twelve, Felipe inched away. “You’re almost a man already,” he had said. “Grown men don’t cuddle.”

There were lots of things grown men didn’t do, and Felipe suddenly wanted to make sure Luisito understood the rules. Grown men didn’t cry, of course. But grown men also didn’t go to the mall with their mothers to pick out towel sets. They didn’t sit with their legs delicately crossed at the ankles. They left their eyebrows bushy, even when the women in the family produced tweezers.

Luisito had been back from school two years now—Brown for undergrad, Cornell for a master’s in architecture—and even though father and son lived in the same area code again, they were only drifting farther apart. They checked in by phone every few days, but they seldom managed to get together. When they did, there wasn’t much to discuss. It was too hot. The price of gas had gone up again. Yes, Luisito’s work at the big firm was going well. Yes,

Felipe still played dominoes with his old buddies from the University of Havana.

But Luisito had no real sense anymore of how Felipe filled his hours away from the restaurant. And Felipe didn’t dare ask too many questions of Luisito. It didn’t help that Luisito couldn’t stomach Felipe’s hard-line on everything to do with Cuban politics. They had gone at it time and time again. “How did I raise a socialist right under my own roof?’’ Felipe had yelled more than once. “How are you my son?”

A few weeks ago, Luisito had gone to see a famous jazz pianist from Havana who had headlined many times in Manhattan but was risking a Miami show for the first time. A mob of white-haired protesters waved Cuban flags, while a younger, courser crowd hurled obscenities and fists at ticketholders filing into the theater past bomb-sniffing dogs. Luisito regretted that he’d never be able to tell his dad about that night. Felipe might have been proud of him for sitting there with his stomach clenched against the urge to sob, feeling deeply Cuban as the hated communist pounded out a surreal “El Manisero” followed by a Havana-infused version of “Autumn Leaves,” which happened to be his mother’s favorite.

They got to the latest fixer-upper, a two-story Spanish Mediterranean on a generous lot, before the realtor arrived. Felipe went around the back and pushed open a swollen kitchen door. Most of the arched windows were busted and the vaulted ceiling in the dining room was starting to cave in.

But, oh, the cobalt tilework, the flamingo frieze above the Deco limestone fireplace, the courtyard littered with blood-red hibiscus flowers. Carried away by the potential of this new find, Luisito make a stupid confession: “Last weekend I went to an opening at the Valls Gallery and I bought an amazing photograph, really huge, that would be perfect above this fireplace!” The artist, who still lived in Cuba, captured a lacy refraction of light across the bluest swimming pool, in which he had floated giant white paper boats, all of them imprisoned by their concrete borders.

“You mean that place that sells overpriced art by a bunch of maricones with their noses up Fidel’s ass?” Felipe pulled a cologne-doused handkerchief from his back pocket and pressed it to his temple, though a cool bay breeze played through the empty house. “That’s what you do with your money? You give it to the regime?”

“It is my money, Papi. So all of their art is worthless because they happen to live on the island? I don’t know why I keep trying to talk sense to a dinosaur!”

“Your money? Maybe you should be counting on your money and not mine to buy the house you want. How much did you pay for esa mierda?” Felipe walked out the front door, but at the landing, he stopped to pry off a piece of the crumbling keystone, encrusted with swirls of ancient sea life. Coquina, it was called in Cuba. His favorite beaches in Matanzas, the ones the tourists never visited, were filled with it. He held a rough shard in his palm, put it in his pocket, then pulled it out and flung it, smacking the trunk of a coconut palm that had grown horizontally across the front lawn.

He stepped back inside. “I’m a dinosaur? And what are you? Artists on the island paint only what Fidel lets them paint. The ones with the timbales to say what they want to say are still being persecuted and jailed, and here it is 1992. You see brave commentary in that photo you bought? It’s all calculated commentary, to help that hijo de puta seem more open these days. So that they can sell art to idiots like you who support the very bastards who destroyed your homeland.’’

“I was born at Mount Sinai Hospital up the street, remember? And I’d rather extend a hand to the younger generation in Cuba, because after all, Castro is not their fault! And that bile is going to kill you!”

Rosalina had died in the same hospital a decade earlier. The cancer spread quickly, turning her into a shrunken viejita virtually overnight. But in her last days, she had spoken with a force and clarity that seemed otherworldly.

“Luisito, mi niño, you’re going to live your life however you want. I’ve always accepted you. But your father, he never will. Don’t break his heart. Get married and have a family the way God intended. Nobody has to know what you do on the side.”

The morning after the quimbombó incident, Felipe was eyeing the newest guy, who was mashing mounds of garlic for sofrito, when a solemn-faced waitress came to the kitchen. “I’m sorry to bother you, Don Felipe. But there are people here for you.”

In the dining room, one of the visitors was holding a wet rag to his nose. La Rampa always passed inspection, but this time, two men from the state took notes while they popped lids off storage containers, poked their heads into refrigerators and freezers and stuck thermometers into cooked hams and marinating chickens. By the time it was all over, the inspectors had uncovered seventeen violations, from mold in the ice maker to fetid rags being used by wait staff to meat kept in coolers nine degrees too warm.

Luisito’s pager buzzed itself off a nightstand and fell apart on the marble floor of his rented Mid-Beach apartment. He was searching for the battery under the bed when the landline started ringing.

“I’ve been calling for fifteen minutes!”

“Qué pasa, Papi?”

“I told you somebody wanted to ruin me! Didn’t I tell you? And some maricón must have called the media. There are four news trucks outside. They’re interviewing people at the takeout window!”

* * *

In the early 1960s, when Felipe was an assistant professor of marine biology at the University of Havana, the new Castro government began its campaign to purge the faculty of any elemento contrarevo-lucionario. He spent three years in a rural prison for subversion, for grumbling to colleagues about the other professors who were

being arrested for nothing. He chopped sugarcane by day and chewed it by night to take the edge off his hunger. There was no trial, no sentence. He wasn’t sure he’d ever get out, but in case he ever did, he started learning English from the professor of philology who shared his cell. Cerca, “near.” Lejos, “far.” Cuando, “when?” Pronto, “soon.” They also shared a safety pin to pop the blisters that formed on their scholars’ hands after those endless hours of forced labor in the fields.

Felipe and Rosalina arrived in Miami in 1965 and slept on the floor of a studio apartment belonging to cousins of hers who worked as bellboys at side-by-side hotels on Collins Avenue. Three days after landing, Felipe strolled into Suwannee’s Seafood House and made an impression on the owners, bearded brothers from backwater Florida who had moved down to Miamah in the 1940s. Felipe’s English was “as good as them refugee Cuban bankers down on Eighth Street,” the brothers figured out quickly.

After three weeks as a busboy, they promoted him to oyster shucker. Two weeks after that, he was a waiter in burgundy vest and matching bow tie. It was much cleaner work, but when he got to their first tiny apartment at one or two in the morning, his pockets stuffed with ones and fives, he still had to throw his clothes in a bucket of water and borax that Rosalina left for him in at the kitchen’s threshold. She was pregnant with Luisito, and even the faintest whiff of fish turned her stomach. Felipe would plunge his uniform, his underwear, and his socks into the bucket—and then, before showering, he’d stand naked at the kitchen sink, rubbing a mixture of lemon juice and sugar into his hands like a surgeon.

One morning, before Felipe punched in at work, the brothers sat him down to tell him they were planning on moving back north to set up a fishing camp near the mouth of the Suwannee River.

“Miamah’s gettin’ outta hand,” one of the brothers said.

“What about this place?” Felipe was already running through a mental list of other decent restaurants that might hire him.

“That’s the good news, son,” the other brother said. “We’re gonna lease it to you! A little later, maybe we’ll even let you buy us out. The Beach could use a good Cuban restaurant. Why should the mainland have them all? You got the smarts. And that wife of yours sure can cook. You just find five grand for a down payment and it’s yours.”

Felipe had a little money tucked away, but nothing close to that. “Look, you want to get back home. Believe me, I understand. I can give you one thousand dollars upfront, and send you a hundred a month, with interest, until I’ve paid off the rest.”

Felipe changed the name to Restaurante La Rampa, a reference to a section of Calle 23, the main street through Havana’s Vedado neighborhood. He and Rosalina moved there, just a few blocks from the university, soon after they were married. On Sunday mornings, when life seemed already so settled, they’d stroll the bustling La Rampa down to the sea, holding hands and fantasizing about their next apartment, which would have higher ceilings and

a water view.

Restaurante La Rampa served fish every day like Suwannee’s had, but it was most popular on Fridays, when the Catholic clientele demanded it. After Rosalina gave birth, she’d come in to direct the boiling of grouper heads for silky, golden soup, and the frying of whole red snappers fragrant with garlic and cumin. She also taught the kitchen staff to cook roasted pork that could melt in your mouth, black bean soup thick like chocolate batter, arroz con pollo creamy as risotto. Soon the place was so busy Felipe had to hire a girl just to handle the line at the door. By the time Luisito was seven, the Mirabals had made enough money to buy a boxy but roomy house at the edge of the Alton Road golf course, a towering Royal Poinciana ablaze in red blooms on the front lawn and the two mango trees out back heavy with fruit.

* * *

Luisito pulled up to the house, which seemed to have gotten a fresh coat of white since he last visited, to drive his father to the cardiologist. His blood pressure had been dangerously high since a couple days earlier, when the inspectors showed up. Luisito found Felipe out front, gazing up at the poinciana though it was too early in the summer for blooms.

“There’s something I want to say.” Felipe groaned as he dropped into the passenger seat of Luisito’s roadster. They were finally leaving Mount Sinai, where the cardiologist, an old buddy of Felipe’s from school, increased the dosage of his hypertension meds and instructed him to take a few days off from work—starting immediately.

“Just listen for a second before you start with your attacks,” Felipe said. “Let’s say there’s no developer trying to get my restaurant to fail.”

“OK. Let’s say that.”

“What if I’ve been infiltrated by spies instead? I can’t sleep since I started turning this over. I should fire the new guy, the one who claims he escaped Cuba on a Jet Ski that he stole from the resort where he worked. Don’t you think there would have been something in the paper? Remember those two Cubans who windsurfed here? They were in the news for days.”

“Wait, wait. Spies from Cuba? Are you crazy?” But Luisito didn’t have it in him for one of his usual tirades. He was suddenly feeling a tinge sick. Maybe Felipe was acting a little—well, not exactly crazy. But, spies? Could his father be showing signs of dementia? How old was he now, seventy-three?

“Why not spies from Cuba?” Felipe raised the passenger window against the wind whipping through the open convertible. “They’re crawling all over Miami. That’s been more than proven! They’re sent here to gather information and wreak havoc. They probably know I give a lot money to anti-Castro groups. They have to have

a file on me still, from the prison days. They keep track of their enemies.”

Luisito was caught off guard when his eyes misted over, but he looked away before Felipe noticed. His father’s generation was still so traumatized. Three decades into exile, they were still unwilling to leave the past in the past. His father was going to stoke his pain until the end, and take it with him to the grave. Just like his mother had done.

And Lord knows that whole generation was paranoid. After all, it was a Cuban exile fleeing Castro, Luisito had discovered a few years back, who had come up with the classic Spy vs. Spy cartoon. He still had a stack of the Mad magazines in which they appeared, magazines he had cherished even before knew there was anything Cuban about them.

“I never bothered to tell you about the castor oil,” Felipe said. “I found a liter of it in the storage room. It was hidden behind the big cans of tomato sauce. Now, you tell me—what was that doing in my kitchen? If that gets poured into the food, my customers would have the shits for days. That’s probably what was in the quimbombó.”

“I’m going to try to look into all of it, Papi. But promise you’ll stay home for a few days and rest, like the doctor said.” Luisito asked for time off from the firm where he was helping draw plans for a chain of resorts angling to blanket the Caribbean. He arrived at the restaurant the morning after the cardiologist appointment with a fruit smoothie in one hand and his father’s briefcase in the other. He hadn’t spent much time at La Rampa lately. He was a vegetarian now and his “neurotic diet” was one more disappointment to his father, who would look at him in disgust when he rejected La Rampa’s celebrated boliche roast, orange grease dribbling from its chorizo-impaled center. The sweet smells of espresso brewing, milk scorching, and buttered Cuban bread toasting in the sandwich presses for breakfast reminded Luisito of his childhood, when he’d go table to table doodling on regulars’ paper placemats. He had to turn them over for white space; their fronts were crowded with illustrations of historic Cuban landmarks. When he got sleepy, he’d crawl under the skirted silverware table for naps, pretending he was a soldier bunking down in a fort.

Now he walked into the kitchen with the official list of violations in his hand, as the cook was taking delivery of onions, plantains, potatoes, some kind of greens.

“Do you want to inspect this stuff?” Rufino looked glad that Luisito had finally shown up.

“No, Rufi, you do it. I don’t know what a good potato looks like.” Felipe didn’t believe in delegating and had never entertained the idea of hiring a manager. Maybe now was the time to find someone, or move Rufi into the job. But how would he convince his father?

The chicharrón guy was hefting a giant pan of pork rinds that had just come out of his fryer. It was that juicy meat attached to the crisped layer of skin that made La Rampa’s chicharrones the most sought after in town. Luisito watched him scatter fistfuls of salt over them, his veins running like purple ropes down his arms. The man grabbed tongs to offer him one of the golden-brown rinds, and Luisito realized he’d stared a beat too long.

“How’s your father?” the chicharrón guy asked.

“Worried.” Luisito was careful not to make eye contact. “I’ll be in the office if anyone needs me.”

The violations seemed easy enough to correct. Luisito started by ordering a new ice maker and two boxes of kitchen linens. The coolers had just needed maintenance. When the repairman came that very morning and started swapping out compressor relays and condenser coils, Rufino, who had been in charge of the cook ing for more than a dozen years, leaned in to watch.

“I told your father a long time ago that he needed to call some body to fix the refrigerators,” he said. “One night he decided he was going to fix the one out front himself. In the end all he did was wipe the dusty coils with a rag. And he must have forgotten to plug it back in. The next morning he was looking for someone to blame. El pobre. He’s getting old, you know.”

A guy from the kitchen supply showed up with new towels. “There’s already several boxes of them in the storage room,” one of the waiters told Luisito. “Your father seemed to be stockpiling them, but he never let us open them. I’m not sure what he was waiting for.”

The last time Luisito remembered being at the restaurant, the man was climbing bar stools to change light bulbs and hauling fifty-pound sacks of rice with no problem. Luisito hadn’t been paying enough attention. A few weeks back they’d gone to eat at Felipe’s favorite Chinese restaurant, and he’d hardly touched his shrimp-fried rice. The same thing had happened at the diner where they sometimes met on Sunday mornings. Felipe ordered his usual French toast and bacon, but left most on his plate.

It was nearly two in the morning when Luisito left the restaurant, exhausted from reading over time sheets and paying vendors and trying to figure out a better system for dating perishables—one of the tougher violations to fix. He knew he smelled like onions and grease, but he walked over to Maelstrom anyway.

As usual, there was a crowd of older men sitting at the tables out front, where you could have a conversation without having to scream over the pounding house music inside the club, the domain of buff boys in cutoffs and Doc Martens. Luisito rarely hung out in the patio, afraid his father might drive by one night and spot him with all of those maricones. But it was late enough, and the last thing he needed was to strobe out on the dance floor with a mob of shirtless guys high on Special K. What he needed was a cold beer.

“Oye, jefe!”

Luisito turned to see the chicharrón guy leaning against an olive tree aglow with tiny lights. He wore stiff Levis and a black button down that showed a hint of chest hair at the collar. Body hair was becoming a strange sight on South Beach, where all the boys pumped iron and waxed, and looked like legions of smooth Roman statues.

“Álvaro Roque,” the man said and extended a hand. “Do you know that in Havana, La Rampa is the street where all the gay people hang out?”

“That probably wasn’t true when my parents were still in Cuba.” Luisito looked around for a server. Now the whole restaurant would confirm he was gay. He didn’t give a damn about the staff knowing, but he needed to protect his father from another blow right now.

“Did you find your spy yet?” Álvaro swallowed the rest of his Heineken. “Don’t worry, your father tells me everything. I go over to the house sometimes and help him with the yard for a little extra cash.’’

“Maybe you’re the spy. What do you know about castor oil?” Luisito tried to take on Álvaro’s teasing tone, but he was suddenly self-conscious about his clumsy Spanish. Álvaro was one of those Cubans who spoke unhurried, luxurious Spanish, pronouncing every consonant.

“I know it’ll give you diarrhea,” Álvaro said. “The sandwich guy, el nicaraguense, gave a big bottle of it to your papi a few weeks ago when he was complaining that he had been stopped up for days. You know Cubans don’t get enough fiber. Your dad never drinks water, either. But I’ve been trying to change his ways.”

“And my dad listens to you?”

“I was a doctor in Cuba. But who wasn’t? You should spend a little time with your viejo, you know. He’s lonely. And, look, forgive me for saying this—maybe you stay away because you don’t want him to know the details of your life. But he already knows.”

“My father told you I’m gay? Does he know you’re gay?” Luisito needed that beer.

“He told me he prays one day you’ll find a quality person to be with.” Álvaro motioned to a server. “And, yes, he knows I’m gay because the first time I went over to help him with the yard, I let drop about my ex-boyfriend the orchid specialist.”

Luisito bought Álvaro another Heineken. And then another. They talked about the trellis Álvaro was helping his father build so they’d have room to hang all the orchids he was growing these days. And about Álvaro’s horrific three days at sea, about the bud dies who had pushed off from Cuba with him on a moonless night and disappeared a few hours later, unable to hang on when twelve foot waves started knocking their raft around.

But Álvaro insisted he didn’t want to dwell on the ugly stuff, so instead he talked about whitewashing the house, while Felipe stirred pails and brought iced water and shots of espresso, and later his homemade fried chicken and macaroni salad, which they ate on a blanket Felipe stretched out on the lawn. Luisito was wide eyed at all of it. His father growing orchids? Making picnics? Whenever he would get stuck, unable to find the word he wanted in Spanish, he’d say it in English, and Álvaro managed to guess what he meant.

“I have an idea,” Álvaro said. “How about you teach me some English and I’ll teach you some Spanish? And there’s probably other stuff we can teach each other. For example, I happen to know a few things about tending to rare orchids.’’

When Maelstrom closed at five in the morning, the last of the boys pairing up and stumbling off, Luisito and Álvaro walked down to the pier to watch the sun rise over the Atlantic. Pier, “muelle.” Olas, “waves.” Una cita, “a date.”

They parted on the sidewalk in front of La Rampa. Álvaro had chicharrones to fry. But later that morning, they’d agreed, Luisito would join him and Felipe on a trip the two had planned to a farm in Homestead that grew the craziest orchids of all.

Luisito turned to leave, but then turned back. “Wait, what about the quimbombó?”

“That will go down as one of the great mysteries. I had a bowl of it before your father decided it was bad. It smelled like regular quimbombó to me.”

The phone woke Felipe, who had spent another night on the sofa. He was still in his trousers, the TV replaying the highlights of a soccer match. Luisito was on the line saying he was going to join him and Álvaro in Homestead today. How the hell had that come to be?

“Maybe we’ll get lunch after the orchids at this great little Mexican place down there,” Luisito said. “Or, no! We can go for ribs at that barbecue shack near the Everglades. You remember how much you and mom loved the Miccosukee fry bread they make?”

Luisito sounded buoyant, like there was no trouble at all at La Rampa, like there wasn’t at least a giant public-relations nightmare to fix after the violations and the news reports. But something about his son’s tone, so light and so rare, plus the promise of a day with him and Álvaro both, had suddenly lifted Felipe’s spirits, too.

He padded into the kitchen in bare feet to make his café con leche. It had been days since he had seen his slippers. He had searched all of the bedrooms, all of the bathrooms. When they’d bought this house, he and Rosalina had planned on more babies to fill it. They stopped trying after three miscarriages. “Luisito will have a family of his own someday and they’ll use this house the way it was intended,” Felipe said whenever Rosalina suggested they downsize.

She’d groused about all the upkeep but refused to hire even a part-time housekeeper, saying she didn’t want another woman running her house. Felipe came to understand, much too late, that Rosalina kept a sparkling house as a form of self-flagellation. She was always leaving the scent of lavender in her wake as she towel mopped the five bedrooms, the formal living room and dining room no one set foot in, and the few rooms they did use—as if the place had been regularly trampled by a ghost version of the big family she couldn’t give him.

After her death, Felipe had hired a series of cleaning women who didn’t clean well enough or meddled too much. The current one came once a week—just to hide his things. He couldn’t keep track of his keys anymore. Or the mail he was certain he’d set down in one place and would appear days later in another.

Rosalina was already gone when Luisito went off to college, and it was only then that Felipe considered selling the house. “It suddenly feels like an isolation chamber. I may start talking to the walls soon,” he told his son during one of their weekly phone chats, and he immediately wished he could take it back. He was proud of his chamaquito, who took after his papi at least when it came to scholar ship. Luisito didn’t deserve being guilted for chasing his dreams.

Truth was, Felipe knew he’d stay in this house until the end. There was nothing more disorienting than losing your sacred ground, the objects that reverberated with your own history. He had already lost everything once: an entire island, all of his beaches, most of his people. If he sold this house, gone forever would be Rosalina’s sewing room, the Singer that she’d left threaded, her collection of shears still hanging from the pegboard. What would he do with the photographs on the walls, the china cabinet full of delicate things that only came out when Rosalina needed to fill the house with the sound of a crowd, usually selections of old friends from back home, all of them still adrift one way or another, even after so many years in Miami.

Every house on the mainland that Luisito had taken Felipe to see also was way too big for a man without a family. But if his son wanted to throw himself into restoring that last one, qué carajo, he wouldn’t stand in the way. Everything he owned would go to Luisito one day anyhow. Maybe they could redo that crumbled coquina at the front landing themselves. Felipe still remembered enough from his marine-biology days to fill that dried-out pond out back with koi, and keep the water balanced. They could pay Álvaro to help with the work.

He had such an easy rapport with Álvaro. Why not with his own son? He and Álvaro could talk about almost anything while they were bent over the orchids, carefully inserting a single pollen grain from one plant into the slit of another. The first time Alvaro had come over, it was because Felipe had needed an extra pair of hands to help build a toolshed to replace the one that had rusted out. Felipe figured the muscle-bound chicharrón guy, who had just arrived from Cuba, would be grateful for the chance to make a little extra money. Behind the old shed they found a graveyard of orchids in pots, most of them just dry sticks, some miraculously flowering even though Rosalina, who preferred them to cut flowers, had banished them from the house and forgotten about them as soon as they lost their blooms.

“Orchids are naughty,” Álvaro had said. “Not only can they be bisexual, not only can they trick male insects into having sex with them, but they can have reproductive sex with themselves.”

Over the next few months, Álvaro resodded part of the yard, put down fresh pavers, and brought over more and more orchids, with flowers that looked like dancing girls, grinning monkeys, white egrets in flight. So many years in this house and Felipe had rarely spent time in the yard. All along he had been the owner of a tiny tropical paradise. He could spend hours out there now, marveling at the pink ginger and yellow heliconias that he sup posed had always been there.

Maybe that’s how a man should spend the twilight of his life, watching flocks of wild parrots jump palm to palm, and breathing the fragrance of the outdoors instead of the grease of that kitchen. Rufi was younger and stronger, and he could run La Rampa better than Felipe these days. Maybe he needed to figure out how to cede the business to Rufi entirely, like the Suwannee brothers had done for him. Felipe had solid savings, a few smart investments. What more could a man want?

“Nobody needs to know what you do on the side,” Rosalina had said to him when they were just kids, their parents gunning for them to marry. Felipe had been honorable enough, or weak enough, to remain faithful to her all those years, no matter how his imagination wandered. Now he needed to be man enough, if he wanted to save his relationship with his son. His beautiful son, who was smarter than he, and so much braver.

He dialed Luisito. “I want to stop at your place first and see the art with the paper boats. Do you know I was obsessed with those when I was a boy?”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Lydia Martín is an award-winning fiction writer and journalist who spent 25 years covering Miami’s growth and cultural evolution for The Miami Herald. She was part of the team that won a Pulitzer Prize for coverage of Hurricane Andrew. She was twice a finalist for journalism’s Livingston Award, and won a GLAAD Media Award for Spanish-language magazine writing. She also won the 2016 Ploughshares Emerging Writer contest for fiction; and the 2016 Editor’s Prize from Fifth Wednesday Journal, which nominated her for a Pushcart Prize.