AWARD-WINNING AUTHOR AND JOURNALIST

AWARD-WINNING AUTHOR AND JOURNALIST

EL BREAKWATER

BY LYDIA MARTÍN

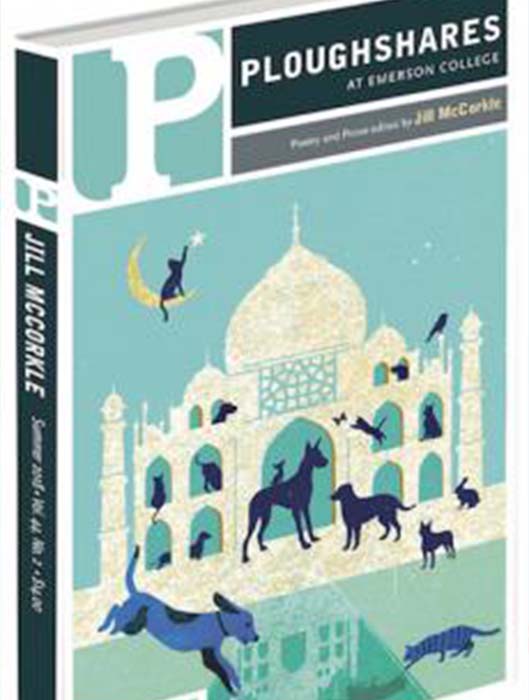

Originally Published in Ploughshares at Emerson College Issue 136

Guest Editor: Jill McCorkle

Date: Summer 2018

The sun hadn’t been up an hour when Angelina and Pablo Ramos tiptoed into the surf at Miami Beach, he sporting his ridiculous plastic nose guard, she in a petaled bathing cap, the rubber strap tight against her chin. The only sound besides the gentle wash of the tide was the fluttering of two seagulls settling on the water. They landed so close to Angelina that she froze, afraid to make a ripple and scare them off.

“Let’s move here already!” Pablo said.

Angelina jumped and the gulls fled toward bleached pilings, their high-pitched ha-ha-ha-ha! like snide laughter in her ear.

“What else do we need besides this sea and these palms?” He was getting louder. “Why do we keep that apartment across the bridge? All those bills. All the cleaning you do. We should be on vacation all the time!”

Angelina teetered back toward shore, her bare feet finding every sharp rock and shell fragment. Pablo splashed along behind her.

They had been a couple for ten years, though they weren’t married. The way they saw it, they’d never need to make it legal, because they already had the same last name. They’d met in Yonkers, when they were both in their early sixties. They took all their vacations to Florida, and as soon as they were able, they moved to Miami for good. They rented an apartment in gritty Allapattah, near enough to their daughters. Each had one; both had fled the north years earlier. And they continued to get away to Miami Beach, delighted that their regular oceanfront hotel was now just a taxi ride across a causeway.

“We can’t live in a room for the rest of our lives. Be serious.” Angelina dropped into her folding chair, driving it unevenly into to the sand. She sat lopsided, eyeing the horizon, pretending Pablo wasn’t looming there, dripping and waiting for her to hand him his towel.

“I am serious.” He reached for the towel himself. “I think I can talk el Breakwater into a discount. But we don’t need to discuss the details now. Let’s just enjoy this beautiful day.”

“We don’t need to discuss the details ever,” Angelina said.

Pablo plopped into his chair and handed her the Coppertone.

“What do you want me to do with this?” Her gaze was still stubbornly on the sea. He pivoted to present his freckled back.

In 1977, South Beach was a tattered resort town, its glory days far behind, but Pablo and Angelina loved those invigorating waves. They were renting their favorite room at the Breakwater for the week and she just wanted to enjoy their daily dips in the ocean, their lazy afternoons in lawn chairs, sand underfoot, sipping icy pineapple sodas from the Styrofoam cooler.

“Do you realize how much cheaper the rates are by the month? Much cheaper than by the week,” he said. “If we moved here for good, there would be extra money for you to spoil your granddaughter even worse than you already do.”

Mostly, Angelina tuned him out when he started up. Mostly, he backed off. She had been clear that she wasn’t interested in giving up their apartment just ten miles west, or in leaving behind the neighbors they’d only known a few years but who were like family—to her if not to him. It was beyond depressing, the idea of paring their possessions down to almost nothing in order to squeeze into one musty room with a leaky air conditioner in the window. She wasn’t ready for the end, for the dismantling and contracting it required.

She worked the Coppertone into his shoulders, still strong like his chest, though now his chest was covered in a fine white down. She wiped what remained of the lotion on her knees and leaned back, hoping for a nap. If real sleep didn’t come, pretending worked just as well. She had learned long ago that placating men, at least in the short run, could be achieved simply by clamming up. No point in saying the next thing, which would only lead to his saying the next thing.

“So what are you going to wear tonight?” Pablo finally said.

“My pink gown?”

“I guess that works for me,” he said.

She’d take this as a truce for today. Angelina reached for a cold drink and noticed the slight tremble of her hands, and her cheeks suddenly felt flushed. Had she forgotten to take her blood pressure pill again? She replayed rising at dawn, tamping coffee down with a teaspoon, and setting the espresso maker on the blue flame of the tiny stove. The milk warming on the other burner spilled over just as Pablo opened his eyes. She had taken the time to scrub the stove after their café con leche and cornflakes. But yes, after that, she did line up her pills and Pablo’s, and they’d shared a glass of tap water to gulp them all down on their way to the ocean.

They could afford to check into the Breakwater, with its optimistic streamline design, its broad front porch resembling the deck of a cruise ship, three or four times a year anyhow. Sometimes they stayed more often than that. When Pablo’s tan started fading, when he glanced out of their apartment window and saw nothing but the parking lot, clotheslines drooping with boxers and bras and a few scraggly trees beyond that, he felt the call of those turquoise waves surging only fifteen minutes away and was insufferable until they made the next reservation at their hotelito.

Even the fancier rooms—facing the beach and big enough for a vinyl sofa the color of pea soup, plus a kitchenette with two folding tv trays tucked between fridge and wall—cost just $85 for a seven-night stay. Between their government checks and their respective bit of savings, they could pay their rent at home and have the beach too. Angelina wasn’t ready, would never be ready, to live the rest of her days confined to a faded hotel full of shuffling retirees. Even if that hotel was just across the street from the Atlantic. God’s Waiting Room, as the southern end of Miami Beach was called because so many old folks moved there, would have to keep waiting for Angelina.

It was Pablo’s fault they had moved to the Allapattah apartment in the first place. They had dragged their winter coats, boots, galoshes, and gloves to the Salvation Army the day before boarding the last LaGuardia—Miami flight they ever intended to take, and as the moving truck made its way south, he limited them to looking for places in a part of Miami he now despised. Angelina had argued for an apartment in a quiet pocket of Little Havana, near her daughter, Soledad, and her granddaughter, Lena. But Pablo wanted to be closer to his daughter, Eneida, who lived just north of downtown, and he’d never budged from the idea that Eneida and her husband, who, after all, were childless, needed their company more. Never mind that Soledad was alone with a young daughter and could use a helping hand.

“Sole has her friends. And she won’t waste time finding the next man,” Pablo said. And Angelina had let him win.

They signed a lease on a bright one-bedroom that was twenty blocks west of Eneida and her husband, Alex, the linebacker-sized telephone company engineer who never opened his mouth except to stuff something in it. The couple, in their mid-forties, seemed content with their bayfront condo and its starched staff at the door, and their constant trips to Europe. They were away more than they were in town. Pablo and Angelina saw them every couple of months, if that.

Their own building was a nondescript two-story with external hallways that flooded in the smallest rainstorm and was painted mustard and made even uglier by the iron bars over every window. There were six apartments downstairs, six upstairs, and the yard out back had a barbecue pit someone had put together out of cinder blocks, and a domino table where residents spent their weekends clicking tiles under the broken shade of a tamarind tree.

It was true that Allapattah was one of the grungiest neighborhoods in Miami. But it was also one of the few where blue-collar Boricuas, Dominicans, and Cubans, black and white, all managed to mix together. No snootiness. No divisions. They were all isleños, after all, born under the same kind Caribbean sun. Angelina could walk into any bodega, any dulceria or sandwich shop or five-and-dime and be greeted with, “Que tal, Doña?” Or, “Que lo que hay, mi vieja linda?”

Angelina picked at the loose threads of her flamingo-patterned beach towel while Pablo waded in and out of a calm sea. The business about moving or not moving remained on the tip of her tongue, but what she talked about was the solid blue of the sky, how balmy it was for the end of June, what she was craving for lunch.

“Maybe I’ll order a big sopón marinero.” Angelina drew Xs in the sand with her red toenails. “And a very cold beer.”

“For me, the grilled grouper and yellow rice. But no beer. If I have one, I’ll have two, and it’ll make me too tired for tonight.”

As the beach umbrellas multiplied, transistor radios blaring a tangle of rhythms, Angelina and Pablo swam, they sunned, they read the Spanish paper under the palms. Then they strolled to their usual Cuban greasy-spoon, where you had to yell to be heard over the festive racket of the crowd, something that always felt like being back in Havana to Angelina, but only rankled Pablo.

“Why do Cubans need to yell, even when they’re just talking about the weather,” he said as he took a sticky plastic menu, wiping it down with a wad of paper napkins before opening it.

By four, they were playing canasta with the others in the Breakwater’s lobby. Angelina had to admit that she loved the Deco wall sconces, the clean block of the front desk made from keystone, always so cool to the touch. She loved the worn-out I Love Lucy furniture, the soft curves that reminded her of her living room in Havana. There was a familiar tropical dampness to this lobby, a hint of tart sea air that filled her nose and lungs and lured her into just sitting here for hours, like the rest of the old people did.

After the card game, Pablo and Angelina went up to their room for cool showers and Harry Reasoner, then a catnap to the clatter of the air conditioner. By nightfall they were strolling hand in hand to the Tenth Street Auditorium. She wore her full-length pink polyester gown, sleeveless for summer but with a high, ruffled neck. He was in a suit the color of wet sand and a shirt as pink as her gown. Their shoes were white patent leather. They knew they’d once again make mincemeat out of the old New Yorkers who thought they could mambo and cha cha. “Cha cha cha,” Angelina would correct, whenever she heard anyone say it wrong.

“If we lived here, we could come dancing all the time.” Pablo dug into his pocket for fifty cents, admission for two to the senior parties where four times a year there were heated dance contests. He and Angelina had accumulated a box full of ribbons, even for their foxtrot. But it was their synchronized Cuban stepping—hips and shoulders in play, instinctively breaking on two, moving in time with the clave but never, ever counting—that swept the others to the sidelines.

Angelina checked her fake lashes in her compact mirror. “We already come dancing here all the time,” she tried to keep the edge out of her voice. “You’ve said it yourself, it’s such an easy taxi ride, so pretty at night going over the causeway.”

Benny Moré’s silky tenor was coming from the speakers, over the scorching brass of the Perez Prado band. Pablo led Angelina inside and straight to the center of the dance floor, stopping under the mirrored ball that for once was spinning.

“Look at the king and queen of mambo!” cried Morris Sobol, who in his day played in the horn sections of Miami Beach’s best ballroom bands. Now he was reduced to emceeing at the senior dances over his own record collection. “So pretty in pink tonight. Watch and learn, ladies and gentlemen!” He stepped off the riser to cut in on Pablo. “Señora Ramos, you’re looking muy guapa tonight. Did you ever see Perez Prado’s band live in Havana? I sure did. Listen to that brass! Tasty! I never took my wife to Havana. Do you know why, Señora Ramos?”

“How many times can you tell the same joke, Señor Murray?”

“Morris. But you can call me anything you like. OK, OK, I’ll tell you. Taking your wife to Havana was like taking a sandwich to a buffet!” He howled at his own punch line.

Pablo was shuffling a retiree in a mod tangerine mini skirt across the floor. Leota, Angelina believed this one was called. She towered over Pablo, her crinkly thighs browned like a Thanksgiving turkey. After Leota came Adina. Angelina continued dancing with Morris, who had pretty good moves for an Americano and seemed almost as nostalgic as she was about Havana’s heyday. He was going on about the baccarat tables and the cockfights when Pablo returned, just in time to take Angelina back for a swinging son montuno, the piano’s tumbao too brazen for any of his groupies to follow.

“Cuba gave the world lots of good things,” Pablo said as he twirled Angelina. “But none as good as you.”

As they walked back to the hotel, the briny night air on their lips, he dropped an arm around her shoulders.

“Tell me this breeze is not delicious.”

“No, it’s delicious,” Angelina said.

As Pablo leaned in to give her a peck on the lips, they spotted an ambulance inching down Ocean Drive. It stopped in front of the Breakwater. Angelina crossed herself as they stepped into the lobby ahead of two men in jumpsuits who fumbled with a gurney.

“It’s Mimi. She’s gone. Collapsed outside her room,” whispered the Romanian widow who had moved to the Breakwater from Coney Island a few months back, right after she had put her husband of forty-six years in the frozen ground.

Mimi? Pablo and Angelina drew a blank.

“Oh, you know Mimi,” the widow said. “Always painted her eyebrows on too high.”

Angelina pulled Pablo toward the wobbly elevator. “No, no! Not another muerto being rolled out of here under a sheet! That’s not the last thing I want to see before I close my eyes tonight.”

But he sent her up alone. When he finally returned, almost an hour later, Angelina was in her nightgown, pacing the water-stained carpet. “What kind of vacation is it when there’s always a chance of seeing a body coming through the lobby? What about the last one, the lady on the third floor who died with all those jars of urine in her room? Que horror! Que miseria!”

“What do you want? She shared a bathroom down the hall. It was a long walk.” Pablo stripped down to his undershirt and boxers and started pulling back the flowered bedspread.

“And nobody to help her! Or even to notice she was so sick! Three days rotting in her room!” Angelina was barefoot, her face oily with night cream, her lashes stuck to a water glass next to the bed. “Death, death, and more death! That’s what this place is. You can stay the rest of the week if you want, but I’m going home in the morning.”

“Pero, mi amor,” Pablo said. “They were sick. We still have time to enjoy life. We can leave in the morning if you really want to, but I was just going to tell you—while I was down there just now, the manager said there’s a special. Two nights free if we stay until next Sunday!”

“Sí? What about Delfina?”

Sunday was their neighbor Delfina’s seventy-fifth-birthday party and their building had a plan. Rosita and her husband were bringing helium balloons and party hats. If it rained, they’d be in charge of renting a tent, which they said they could get for cheap. The couple downstairs had a nephew who was a DJ and he was going to spin real merengue and bachata from Delfina’s Santo Domingo. Half the neighborhood was coming. Angelina had volunteered to make big tins of arroz con pollo.

“We’ll show up in time,” Pablo said. “We can get arroz con pollo at one of those takeaway places. Why cook for two days? Nobody will know the difference.”

Angelina dropped onto the vinyl sofa and looked out the window, at the sliver of moon, the sea so black she could only conjure the memory of it. “The building is expecting my arroz con pollo,” she said, barely above a whisper. She started pacing again, fanning herself with a flimsy section of newspaper that did nothing against the heat on her face.

“I can’t be here another day, much less another week,” she finally said, grateful she had not raised her voice. “I’m finished with this place. Se acabó el Breakwater. You can stay if you want. I’m packing and going home tomorrow.”

“Now you’re being ridiculous. But, fine, go,” Pablo said. “I’ll see you next Sunday for the party.”

Angelina departed at daybreak, in a taxi that Pablo insisted on hailing for her.

“Take some time and think about this,” he said.

“The one who better think is you.” Angelina resisted the urge to slam the car door.

From their first meeting, the Ramoses knew they’d be a couple. Angelina had been in the States for a year, after making good on a promise to leave Cuba the next time her husband raised a hand to her. Her brother Emilio, head janitor at a hospital in Yonkers, had sent money for the exit papers and the plane ticket to New York.

When she arrived at his little house on Buena Vista Avenue, he handed her an envelope with enough cash in it for her to buy a winter coat and boots, new curtains, a bedspread, and whatever else she needed for the bigger of the house’s two bedrooms, which he had moved out of after his wife wasted away in there from cancer.

Dinner on the sofa in front of The Lawrence Welk Show became their Sunday night ritual. Angelina spent the day cooking oxtail stew until the meat fell off the nubby bones, fricasé de pollo with raisins plumped in cooking wine, caldo gallego with ham hocks, chorizo and turnip greens—and Emilio ate heaping bowls of whatever she made while he tapped his foot to the music. He would translate every word, Angelina’s first English lessons. At the end of the show, they sang along with the Champagne Music Makers: “Good night, good night, until we meet again. Adios, au revoir, auf wiedersehen, ’til then!”

Pablo, who had lost his wife a couple of years earlier, happened to live in a boarding house two blocks up the street. The owners lived right next door to it in a smaller house; she was from the Dominican Republic, he was from Poland. Juanita Stronski, who had been close to Emilio’s wife, cooked sancocho one day, borscht the next, and delivered it to the bachelors and widowers who rented rooms. She was particularly charmed by Pablo, who always wore a coat and tie and occasionally presented her with flowers and her husband with cigars, which he apologized for because they weren’t Cuban. Juanita had looked the other way when Pablo brought in a hotplate so that he could make his own café con leche in the morning.

“There’s a Cubano who rents from me,” Juanita said to Angelina. “He came after his wife died, el pobre. I want you to meet him. Un caballero. And he has a decent job too.”

The night they both came to dinner, Juanita made stuffed cabbage. Also cod fish fritters and arroz con habichuelas. Pablo showed up with two bottles of Rioja from the supermercado he managed. He wasn’t tall, but he had a chin like Kirk Douglas and he wore a powder blue suit in honor of spring. Every time Juanita got up from the table to get something, he rose too. Every time she returned, he rose again.

“What do you miss most about Havana?” Pablo asked Angelina over flan and Sanka.

“I still think about those beautiful dances from when I was a young girl, the men in their white linen suits and those big orchestras playing danzones. What a paradise it all was before el barbudo turned it all to dirt.”

“I wish I still had my white linen suit,” Pablo said. “Then again, I’d look pretty ridiculous wearing it in Yonkers.”

A week later, he called Angelina to invite her to a dance at El Club Cubano in New Jersey. “I’ll make sure the band plays a danzón or two. My cousin and her husband have a car. We’ll go with them so that I can prove my intentions are pure.”

“I don’t think I need a chaperona,” Angelina said. “Remember I’m a grandmother.” But she giggled more like a schoolgirl.

Soon, Pablo was coming over for Lawrence Welk suppers and singing along at sign-off. “Adios, au revoir, auf wiedersehen!” But he slept in Angelina’s bed only when Emilio worked an overnight shift, and she always made him get up and go before her brother jangled his keys at the front door. Whenever they found cheap enough fare, they’d fly to Florida.

“I can’t leave Emilio alone. Please understand,” Angelina repeated whenever Pablo pushed for them to make good on their plan to move south someday. Then, five years after they had started seeing each other, Emilio fell dead in a hospital corridor, his floor buffer spinning off and crashing into the double doors that led to the emergency room.

Rain was pelting Allapattah when Pablo came through the door, his straw fedora soggy on his head. It had been a little over twenty-four hours since Angelina’s taxi had left him standing in front of the Breakwater.

“The beach is not the same without you,” he said.

Angelina threw her arms around him. She understood his desire to spend the years he had left loafing in swim trunks while the sun inched toward the Art Deco hotels, tinting them in pink and orange before dropping behind their parapets and spires. She understood that while everyone in Allapattah spoke the casual Caribbean Spanish that felt most like home to her, Pablo had lived in Yonkers since the early 1940s, abandoning Cuba not over politics but for an office job at the Domino Sugar Plant in Brooklyn. New York was where he’d picked up a taste for egg creams and sour pickles.

She knew he felt a kinship she never would with the Yiddish-favoring retirees who populated the washed-out hotels of Ocean Drive, that he loved going on capers with the guys, to dive for day-old dinner rolls in the dumpster behind Wolfie’s and feed them to the seagulls, or to sneak into the Raleigh Hotel’s famous scalloped swimming pool, where Esther Williams herself had kicked around once upon a time. They would arrange their folding chairs in the shade of the park that bordered the beach, where they could still hear the waves crashing, and whistle at the girls in bikinis who breezed by on roller skates and bikes.

But Allapattah’s gente were nearly as chevere as Luyano’s, the humble Havana neighborhood Angelina had turned her back on, fleeing not just from the Fidel Castro, who had dragged thousands of decent people in front of firing squads, but from the Fidel Castro under her own roof, the one she had married when she was much too young.

Just a few weeks ago, Angelina was walking home, lugging two grocery sacks, when one slipped and spilled, the sugar flying everywhere and her cans of pears rolling toward the gutter. One of the rough boys from across the street came running—the same one she had seen from her window, shirtless and sanding down to the bare metal a Chevy that Pablo said was likely stolen. He gathered the mangoes and the onions at Angelina’s feet, fetched the cans of pears and wiped them clean with his bandana and then carried everything all the way upstairs to her apartment. He’d refused the dollar she held out but accepted a cold 7UP with a little bow. He called her señora, kissed her cheek, and told her to look for him next time she had too much to carry home from the store. “Me llamo Razor,” he’d said.

While Pablo carried a heavy tin of arroz con pollo, steamed in broth and beer, down to the dusty yard behind their building, Angelina heaped a double serving of it onto a plate and walked it across the street to Razor, whose real name — she’d asked and he’d admitted — was Hilario. When she returned, someone had already strung the little flags, red, white and blue, from the trees. Now she only had to direct where the sunflower-shaped piñata should hang.

“Isn’t Delfina too old for a piñata?” Pablo said. “What did you put in it? Geritol and Ex-lax?”

“No, chico, it’s for the kids.” Angelina swatted his shoulder. “So don’t throw your back out fighting for the candy bars. I saved a few for you upstairs.”

It had been a week since the flare-up on the beach and Pablo hadn’t mentioned moving again. He nursed a rum and Coke as more neighbors showed up for the party. The man sure could charm. There he was in the short-sleeved shirt he’d pressed himself, mint green to go with his summer plaid pants, side-stepping with Delfina to one of her favorite merengues.

When the next bachata began, Pablo looked around for Angelina. He held her close and moved her slowly around the yard. And as night fell on Allapattah, she started feeling guilty for keeping him from his beach. She loved it too. Loved the sea air, the kind of hungry she got after a swim. Maybe she could talk him into a week at the Clevelander instead. It was a little more expensive, but there were usually lots of Cuban families from up north there. People with a pulse, people young enough to still believe life might stretch on forever. Pablo could visit his friends at el Breakwater all he wanted. It was just down the street. She’d propose it in the morning, after making his Cream of Wheat with condensed milk.

After the singing and the cake, Delfina, still in her party hat, threw her arms around Angelina. “Ay, mi amiguita del alma, I’m going to miss you so much.” She wouldn’t let go.

“What do you mean? Where am I going?”

“Pablo says you’re moving to that hotel. When were you going to tell me? He was just asking if I would be OK with you coming back every now and then to stay with me. Of course! Of course you can stay with me!”

Angelina looked around the yard for Pablo, but he had already slipped upstairs. She found him in the kitchen, gulping ice water in his underpants.

“Did you say we’re moving to the beach? Estas loco?”

“I didn’t say when we were moving, mi amor. Calm down. I said we were considering it. I thought maybe if you could come back here whenever you wanted, we would both be happy. But enough with the back and forth. The truth is, I made a call to the Breakwater, and right now, if we pay a whole year in advance, we’ll get two months free. That kind of offer won’t come around again. It’s time to act.”

“Except we have a lease here and it won’t be up for another seven or eight months. Or did you forget about that?”

“What lease?” Pablo refilled his tumbler at the kitchen tap. “We’re month to month.”

“What are you talking about? Since when?” The lease was her one real card to play.

“Since February. Since we decided there was no point in signing another lease because we were thinking about moving. Don’t you remember?”

What she remembered was the day Pablo had insisted at the last minute that she go alone with Soledad and Lena to check out the new Omni mall downtown. Mother and daughter were on the way to pick them both up when he announced he’d have to stay home and miss all the fun. The landlord had called while Angelina was in the shower, he’d said. He was going out of town and wanted to come over right then to get them to sign their new lease. Pablo had negotiated month-to-month terms behind her back.

“You think you can just drag me to die in that place?” Angelina suddenly felt sick, and the tears she tried to conceal spilled anyway. She hurried to the bathroom and locked herself inside. She stood under a pelting hot shower until it went cold. Then she sat on the edge of the bathtub wrapped in her towel, waiting for Pablo to fall asleep before she came out. What could she possibly say to him now?

She remained mute the following day, well into evening. She cooked dinner anyway, because that was the job even of unofficial wives. But he’d have to live with fried eggs over white rice, her usual fuck-you meal. While the rice was simmering, she turned on the tv. The famous fat comedian from Argentina danced around bikini-clad showgirls balancing fuchsia headdresses. Pablo came to sit on the arm of the sofa.

“You know enough English,” he said. “You don’t have to watch the porquería on Spanish tv.”

“I think your baseball games are porquería. But I don’t bother you about it.”

Pablo gave too big a laugh and offered to fry sweet plantains. Another attempt at a truce. But weren’t they beyond truces now? When they sat down to eat, he cleared his throat, then he cleared it again. Angelina put down her fork. Maybe he was ready to apologize.

“You have six weeks to decide what we’re taking and what we’re getting rid of,” he said in the puffed-up way her father and her ex-husband spoke when they were laying down laws. “I told the hotel we’d move in by the start of August. I don’t want to hear another word. And I don’t want any crying about it. I’ve been more than patient, and you’ve been nothing but stubborn. That ends now!”

Angelina stood. She sat again. She stared at her hands in front of her, so pale they hardly looked like they belonged to her.

“I’m not giving up this apartment,” she said so softly it was a near whisper.

“Oh, no? Well, no woman is going to control my life!” Pablo pounded his fist on the table, making the dishes jump. Angelina’s ex used to pound tables too.

A red heat spread across her chest and before she knew she was doing it, Angelina hurled her plate against a wall. Pablo’s hands trembled when he stood, and he slammed the front door on his way out.

In the morning, Angelina woke to find rice and eggs drying on the wall and Pablo stacking shorts, socks, pants, and shirts across the length of the sofa. His favorite suits were draped over the La-Z-Boy.

“I didn’t want to pull the suitcases out of your closet and wake you.” He tucked a rolled-up belt inside his shoe. “I called the Breakwater. Only one room is available right now and it doesn’t have the best view. But we can move to a better room later. You can take a few weeks to join me, if you need to. I’m going now.”

Angelina padded toward the bathroom in fuzzy slippers, as if she’d heard nothing.

“I’m going with or without you!” Pablo yelled.

Angelina took her time showering and dressing, then she sipped her coffee standing at the kitchen sink while he finished packing. When she heard the taxi horn downstairs, she shut herself in the bedroom and blasted salsa on the radio so that she didn’t have to hear him slam the door again.

A week passed. Then two. By week three, Angelina imagined Pablo in the clutches of one of the widows. Ora, maybe. Even under Angelina’s nose she was always fussing over him, coming to the shore to present him with remnants of deli cream cheese sandwiched between saltine crackers. Was he teaching her to cha cha cha?

One afternoon, Soledad came to talk sense into her mother. “You know, he called me last night. He’s waiting for you to change your mind.”

Angelina already had to strain to recall the blue of his eyes. Early on, they had made her swoon. But they were eyes that monitored her all day long and still never quite saw her.

“I didn’t leave two tyrants behind in Cuba to live with another one here,” she said.

“Pero, Mami, what if he really won’t come back? Pablo is not such a bad man. He’s not my father.”

No, Pablo was not Pancho. Pablo had never shown up drunk after a night on the town with God knows what floozy. He had never lost his paycheck at a card table, or busted her lip. But like too many Cuban men, Pablo insisted on wearing the pants. They always ate what he was hungry for. Went to bed when he was sleepy. Had sex when he was in the mood. He decided the weeks when they would go to the beach, even if Angelina had other plans. He even picked the clothes Angelina wore when they went out. And the time she came home from the beauty parlor with red hair, he had marched her back the same day and forced her to make it brown again.

“Did I tell you Delfina’s cataracts are getting worse? She can’t ride the bus alone to her doctors anymore. But we go together and we laugh the whole way,” Angelina said. “And Rosita and her husband are having a baby. Won’t it be nice to have a baby in the building?”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Lydia Martín is an award-winning fiction writer and journalist who spent 25 years covering Miami’s growth and cultural evolution for The Miami Herald. She was part of the team that won a Pulitzer Prize for coverage of Hurricane Andrew. She was twice a finalist for journalism’s Livingston Award, and won a GLAAD Media Award for Spanish-language magazine writing. She also won the 2016 Ploughshares Emerging Writer contest for fiction; and the 2016 Editor’s Prize from Fifth Wednesday Journal, which nominated her for a Pushcart Prize.